This written portrait is available in Polish as well (below).

.

.

.

.

Caring through one’s hands

.

Adela collects pepper grinders, of all shapes and sizes, as well as tea and coffee cups. She started collecting things after her homelessness experience. She enjoys collecting so much that she collects people as well, she jokes. Adela cannot imagine life without people and the pandemic makes it very hard on that front.

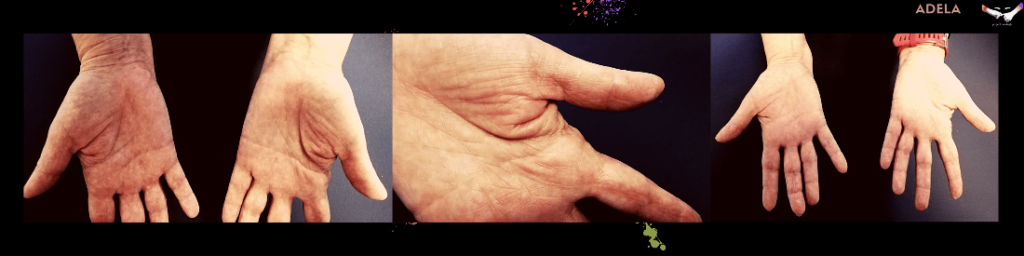

Ola and Adela met during English class in university for seniors. Adela is an aristocrat, Ola jokes. Watching them together, it’s no wonder they got along so well. Adela is 70, she was born and raised in two different cities in Wielkopolska and her hands are quite white, thin and soft. If she didn’t tell me, they wouldn’t reveal how much she worked until her 19th birthday.

Adela was one of 11 siblings and did all sorts of house and farm work to help sustain their home. She worked about double the kids her age and quite early started caring about her hands. But caring significantly for her nails, which were always dirty, only came later, when she started meeting people outside farm life and comparing how their hands looked.

Let’s not be blind sighted by the stereotypes of farm and domestic lives, nonetheless. Her parents had studied abroad, her mother became a doctor and later Adela did manage to go into nursing school. Where she grew up there were only 5 polish families, 5 German and 5 eastern families. Hence, her parents expected her to be proud of her origin and identity, and to speak and behave like a proper polish person, she says.

Adela does still honour her identity. From how to catch fish, choose the right plant for washing clothes, to doing a fire, indeed, everything Adela learned with her mother and grandmother early on, she now teaches her nine teenage grandchildren! And she is happy to be their confident as well. Every year, the family spends two amazing weeks in a lake site together, learning about nature and experiencing a break from the luxury the contemporary world provides, even from cell phones. Everyone is fully there and, be astonished, they talk to each other! Adela hopes the kids will become interested in the world, more independent and resourceful, because nothing is guaranteed, she adds.

Perhaps from nature, perhaps nurture. Adela has this putting-her-hands-to-work way of caring. She tells me that, traditionally, people would greet grandparents by kissing their hand, and she fondly remembers kissing her grandmother. From another point of view, however, she tells me that, as a nurse, she often worked with dying patients. Holding their hands in the last moments of their life was very important and significant for her. Holding out her hands to people in need became an instinct. Being a nurse wasn’t only a profession, it was a vocation. People went into it with all their lives, she says, comparing to the current medical landscape.

Adela has been through some trials, but that hasn’t changed her nature. She was hit by her husband, but she stayed, she loved him. It did take her a long way to divorce, but she left and started over in Poznan. Then, after three decades of owning her own home, she became homeless for a year, for no fault of her own. Still, she doesn’t give up on people, she simply doesn’t. Where others might refuse to touch or even refuse to be close, whatever or whoever it is, she has a natural need to help.

Adela now is in touch with her ex-husband’s lover. She couldn’t ignore somebody in need, even someone who’d caused her unhappiness. Adela is grateful for the life that she has and the people she meets. There are doors we must close from past experiences, she says, but people cannot be overlooked.

.

.

.

Troska poprzez dłonie

.

Adela zbiera młynki do pieprzu, w każdym kształcie i rozmiarze, a także filiżanki do kawy i herbaty. Zaczęła zbierać rzeczy po doświadczeniu bezdomności. Zbieranie tak jej się spodobało, że zbiera też ludzi – żartuje. Adela nie wyobraża sobie życia bez ludzi, a pandemia bardzo jej to utrudnia.

Ola i Adela poznały się na zajęciach z angielskiego na uniwersytecie dla seniorów. Adela jest arystokratką – żartuje Ola. Obserwując je razem, nie dziwię się, że tak dobrze się dogadują. Adela ma 70 lat, urodziła się i wychowała w dwóch różnych miastach Wielkopolski, a jej dłonie są całkiem białe, cienkie i miękkie. Gdyby mi nie powiedziała, pewnie nie dowiedziałabym się, ile pracowała do swoich 19 urodzin.

Adela była jedną z jedenaściorga rodzeństwa i wykonywała różne prace domowe i gospodarskie, aby pomóc w utrzymaniu domu. Pracowała mniej więcej dwa razy więcej niż dzieci w jej wieku i dość wcześnie zaczęła dbać o swoje ręce. Ale dbałość o paznokcie, które zawsze były brudne, przyszła dopiero później, kiedy zaczęła spotykać ludzi spoza gospodarstwa i porównywać wygląd ich dłoni.

Nie dajmy się jednak zaślepić stereotypom dotyczącym życia na farmie i w domu. Jej rodzice studiowali za granicą, matka została lekarzem, a później Adeli udało się pójść do szkoły pielęgniarskiej. W miejscu, w którym się wychowała, było tylko 5 rodzin polskich, 5 niemieckich i 5 rodzin ze Wschodu. Dlatego też rodzice oczekiwali od niej, że będzie dumna ze swojego pochodzenia i tożsamości, że będzie mówić i zachowywać się jak prawdziwa Polka – mówi.

Adela nadal szanuje swoją tożsamość. Od tego, jak łowić ryby, wybierać rośliny do prania ubrań, rozpalać ognisko – wszystkiego, czego Adela nauczyła się wcześnie od swojej mamy i babci, uczy teraz swoich dziewięciorga nastoletnich wnucząt! I jest szczęśliwa, że może być również ich powierniczką. Każdego roku rodzina spędza dwa niesamowite tygodnie nad jeziorem, ucząc się o przyrodzie i doświadczając przerwy od luksusu, jaki zapewnia współczesny świat, nawet od telefonów komórkowych. Wszyscy są tam w pełni sobą i, o dziwo, rozmawiają ze sobą! Adela ma nadzieję, że dzieci staną się ciekawe świata, bardziej samodzielne i zaradne, bo przecież nic nie jest gwarantowane – dodaje.

Może z natury, może z wychowania. Adela ma taki sposób opiekowania się, który polega na przykładaniu się do pracy. Opowiada mi, że tradycyjnie witano dziadków całując ich w rękę, a ona sama z sentymentem wspomina całowanie swojej babci. Z innego punktu widzenia jednak, opowiada mi, że jako pielęgniarka często pracowała z umierającymi pacjentami. Trzymanie ich za ręce w ostatnich chwilach ich życia było dla niej bardzo ważne i znaczące. Wyciąganie rąk do ludzi w potrzebie stało się instynktem. Bycie pielęgniarką to nie był tylko zawód, to było powołanie. Ludzie wchodzili w to całym swoim życiem – mówi, porównując się do obecnego krajobrazu medycznego.

Adela przeszła kilka ciężkich doświadczeń, ale to nie zmieniło jej charakteru. Była bita przez męża, ale została, kochała go. Długo trwała jej walka o rozwód, ale wyjechała i zaczęła od nowa w Poznaniu. Potem, po trzech dekadach życia we własnym domu, została na rok bezdomna, nie ze swojej winy. Mimo to, nie rezygnuje z ludzi, po prostu nie. Tam, gdzie inni mogą odmówić kontaktu lub nawet bliskości z kimkolwiek lub czymkolwiek, ona ma naturalną potrzebę pomagania.

Adela jest teraz w kontakcie z kochanką swojego byłego męża. Nie potrafiła zignorować kogoś w potrzebie, nawet kogoś, kto był przyczyną jej nieszczęścia. Adela jest wdzięczna za życie, które ma i za ludzi, których spotyka. Są drzwi, które musimy zamknąć z powodu przeszłych doświadczeń, ale ludzi nie można pomijać.

.

.

Follow the Instagram page of Project Handsight / Śledź stronę Instagram projektu Handsight

We’ve prepared an exhibition for the windows of Inkubator Kultury Pireus. You can still visit it until the second week of April/2021. Check the event on Facebook!