Here in Poznań, I am certainly miles away from the Philippines – geographically at least. But what nearly four years of being away has taught me is that it’s no cliché we carry our homeland with us always, with all its beauty, ugliness, tragedy, and complexity no matter how far away we go and no matter how deeply our experiences abroad change us (and they will, no exception).

Let me backtrack a little and explain what makes the Philippines complex and tragic.

The Philippines is spread over thousands of islands in Southeast Asia. Pre-colonial society was a collection of Malay kingdoms and tribes similar to Malaysia and Indonesia, and when the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, these two populations merged, displacing previous populations and isolating the Muslim South. 300 years of Hispanisation brought with it Catholicism, education of the elites in prestigious and exclusive religious schools, and fetish for lighter-coloured skin as proof of Spanish descent; all these continue to the present. This time also brought about many abuses, leading Filipinos educated abroad to create literature and art demanding justice and equal rights. Inspired by this, the educated class at home organised the Philippine Revolution which was unfortunately halted by the sale of the Philippines to the United States. The Philippines would then pass in quick succession from Spain to the United States to Japan, and back to the United States, before gaining independence after World War II, become a democratic state, then suffer twenty years of a dictatorship, before regaining an unstable democracy. Each brought with it historical trauma, and a human price of livelihood and stability at the least, and blood and life at the worst.

I personally don’t believe in sugarcoating a country’s experience, so to promote to others only its positive aspect because I feel this trivializes the people’s progress, as well as their suffering.

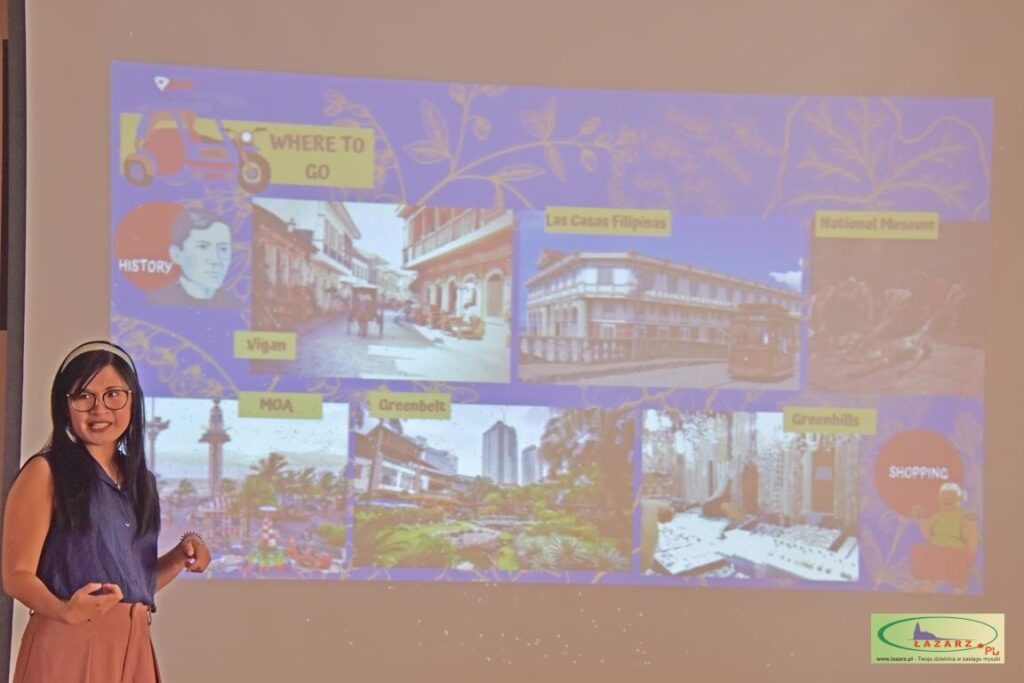

So this is the Philippines I presented to my small but very engaged audience at Krag: a country that has vast swaths of natural beauty and admirable examples on the fight for democracy, certainly, but also a state in conflict with itself. My Philippines is one with considerable disparity between the rich and the poor, where the quality of education and the possibilities for women are intrinsically tied to social class, where individualism hinders the progress of the country as a whole.

I presented what I hope was a brutally honest account, and I’d like to think this is what engaged my audience, that perhaps a shared history of generational trauma and persisting social ills may be what encouraged them to ask questions; centuries of conquest, integration, and overlapping identities, followed by a post-War period of totalitarian rule. Because their questions were not about quaint topics like touristic attractions, or even the food, but the deep end of the pool, so to speak: unequal education, prostitution, poverty, the questions they asked were about the people themselves and the lives they lead, with all its tragedy, complexity and darkness.

Perhaps, this exchange can show that discussing the more unsavory aspects of a nation, discussing how this experience can in fact be shared between cultures that developped on opposite sides of Europe, can be a means to heal.